Tiny Tip: Consider Big Numbers Carefully

This post is the first in a series on tiny tips for becoming a more informed readers of numbers, charts, and data stories. My intent is to help people become more informed data consumers, but also give some food for thought to data communicators around how we can visualize data more responsibly, citing our sources and making sure to put numbers in context.

My career in public health started as an analyst. My team was responsible for creating website content for USAID: profiles of the HIV situation in different countries, presentation decks, and reports to Congress.

Each year, compiling reports to Congress relied on analyzing USAID data on the counts of people who received services, medicines, distributed, etc.) and population health survey data. (Note that some of those sources, like data requests to the Demographic and Health Survey Program, are paused thanks to the current stop work order.) We also met with staff to distill out the ‘ultrafabs’ - the ‘ultrafabulous results - that would make the case to Congress that the money spend on foreign assistance and specifically global health was worthwhile.

It never felt like a hard case to make. We had numbers to quantify the millions of lives saved thanks to USAID support for nutrition programs, prenatal care, medicines for HIV and malaria, and so much more. Making the case for global health funding seemed easy in part because we all believed deeply in the mission and impact of the work.

But year by year, foreign assistance, including global health funding, always seemed up for debate.

Big numbers shape public perception

Challenging the benefits of foreign assistance spending isn’t new. But the Trump administration has taken questioning the value to new heights, shutting down the entirety of USAID for a 90 day stop work order that has sparked furloughs, layoffs, and massive impacts to programs around the world that provide food, health care, security, and other services to beneficiaries around the world.

“This is not a pause. It is destruction,” wrote former USAID Administrator Atul Gawande (The New Yorker). For workers in the sector, broad estimates have ranged as high as more than 50,000 jobs lost when the dust settles (LinkedIn). While my many global health colleagues are even more devastated by the impact to people around the world with the collapse of programs that benefit millions than the loss of their own livelihoods, it pains me to see others celebrating or at least passively accepting that stopping ‘foreign’ assistance is a data-informed decision freeing up needed money in our federal budget.

Which reminds me just how misunderstood our spending on foreign assistance is by those outside of the sector.

Even what gets called ‘foreign aid’ and nerdy distinctions between ‘foreign aid’, ‘foreign assistance,’ ‘international development,’ ‘USAID spending,’ and other framings cause confusion, skewing perceptions many people in the US have around the scale of foreign assistance spending.

Take this teaser from a Fox segment last year, focused on a $95 billion national security bill framed as ‘foreign aid.’

That $95 million isn’t a USAID appropriation, yet seeing those kinds of big numbers fuel the perception of far more funding going to the Agency than we’ve ever seen.

Ask Americans how much we spend on foreign assistance and the guesses are typically around 25% of our federal budget, with a preference to keep spending around 10% (Brookings Institute). But what share of the federal budget does USAID really account for?

Today’s tiny lesson: Consider big numbers carefully.

Consider the relative scale: $42.8 billion or <1%?

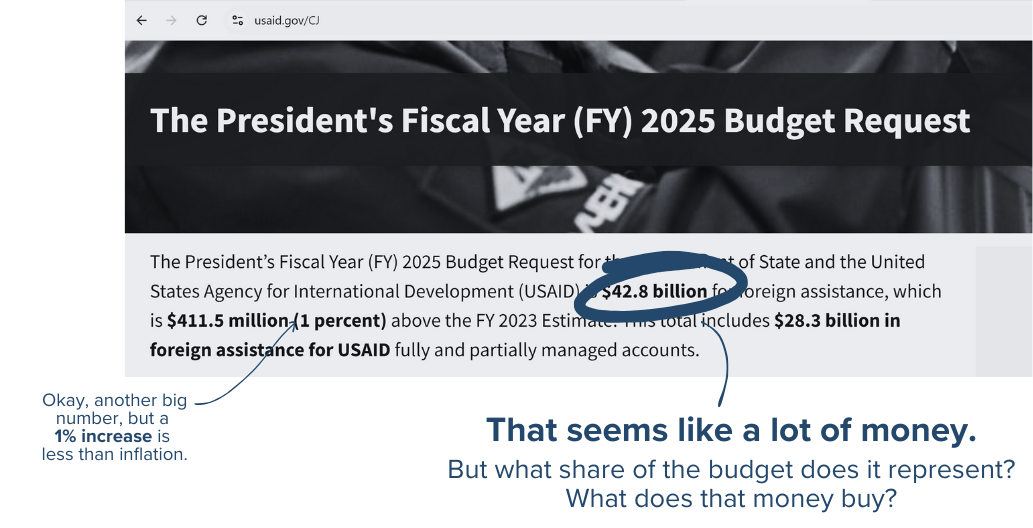

The FY2025 budget request for the Department of State and USAID was $42.8 billion dollars for foreign assistance. Of that money, $28.3 billion, or around two-thirds, was designated for USAID (USAID).

Those both sound like REALLY big numbers if you’re comparing the spending to your own household or even a small company.

But in the scale of the $7.3 trillion US Government budget, it’s miniscule: less than 1% of the total, which is consistent with the small share of our budget appropriated to foreign assistance over many years. Less than 1%: not 25%. USAID represents an even small share, typically less than 0.5% of the budget.

So here’s the first half of today’s tiny tip to make sense of data: when you see big numbers, pause and consider the big picture. For big funding numbers, how much is this line item relative to the overall budget? What does this level of spending pay for?

Annotated screenshot from usaid.gov

Samantha Power, former USAID Administrator, pointed to key strategic priorities that money supports, and it’s a far broader scope that you might think.

USAID funding supports humanitarian responses to crises around the world, addresses food security challenges, boosts economic resilience through investment in private sector growth, champions global health and health security in our hyper-connected world, and even explicitly aims to out-compete China.

Development work exerts a soft power and bolsters goodwill in ways that complement our defense and diplomacy efforts, at a fraction of the cost.

Consider trustworthiness: $50 million for condoms in Gaza?

Take a different big number tossed out in press conference and later repeated by Trump: “We identified and stopped $50 million being sent to Gaza to buy condoms for Hamas. They used them as a method of making bombs. How about that?”

$50 million also seems like a lot of money.

It’s a data point teed up to shock and awe, especially with the added political lightning of mentioning Gaza. And the assertion that we’re buying condoms that are used to make bombs? Seems incredulous.

But does that number even seem feasible? Consider that USAID procures condoms for around $0.05 each. $50 million would mean sending 1 billion condoms to Gaza, which makes absolutely no logical sense for a population that was estimated at just over 2 million (Jeremy Konyndyk).

Some fact checking by news outlets confirmed that statement was wrong. Maybe someone misread a spreadsheet or dashboard? The line item in question was for USAID funding supporting health clinics in Mozambique - including in the province of Gaza (FactCheck.org). Not a bulk order of condoms.

Second half of today’s tiny tip: look for the data source, particularly when a data point seems suspicious. Yes, fact checking takes time, but remember that data is not objective. The more we roll up small numbers into big ones, the more opportunities we create to set our own rules around what is included in that aggregation; the more rushed we are to shape public perception with big numbers, the more likely it is that someone makes a mistake.

Knowing the data source can help you evaluate the trustworthiness of the number. And if the source isn’t available, consider other ways to validate whether its a reliable figure (again, $50 million would buy 1 billion condoms…).

A footnote on disappearing data

Writing this post the morning of Saturday, February 1, 2025, some of the sources I would typically use for data points on USAID budgets and spending, like ForeignAssistance.gov, have been taken offline as the current administration is removes access to information.

You can still find data through some of the archiving efforts underway - more on that from the Harvard Library Innovation Lab Team - though many of us in the public health world are concerned not just by the disappearance of existing information, but what data will be collected over the next four year (or not). When an administration doesn’t want you to have access to information, it’s a tactic not an accident.